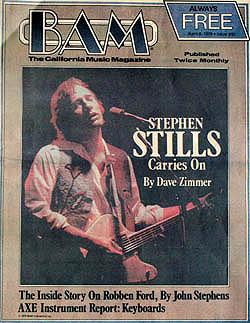

Stephen Stills Carries On

By: Dave Zimmer – “BAM: The California Music Magazine”

Photos: Henry Diltz & Jim Marshall

Date: April 6, 1979 and exclusively re-issued on 4waysite.com in 2007

Los Angeles – Ambitious, blunt but expressive, forceful, aggressive when the occasion requires it, capable of manic dedication and drive towards work and life goals… a few choice character traits an astrologist would say a Capricorn may exhibit. Stephen Stills, born smack in the middle of this sign of the zodiac, should someday have them chiseled as his epigraph.

Evidence of Stills’ musical dedication appears throughout his two-story brick and mortar estate in Bel Air. A small silver platter bearing in bold blue letters – “Buffalo Springfield” – leans against a bookcase; the interlocking Crosby, Stills & Nash logo is pressed into a varnished block of wood on a low shelf; framed Stills and CSN concert posters hang in a main hallway, and downstairs in his den/music room, several gold records adorn one wall.

But Stills, at age 34, doesn’t appear ready to rest on his laurels. He’s now focused on revitalizing his solo career that has been idling ever since CSN regrouped in ’77. With a new group, and in the midst of a solo tour, Stills is shifting into a fresh, wide-open largely electric style of play. The first notes of the current tour were historic ones as Stills, along with several other CBS recording artists, performed in Cuba at the Havana Music Festival. For the first American-Cuban music event ever to take place on the socialist island, Stills sang a song in Spanish that he wrote for the Cuban audience. He subsequently took Irakere, an Afro-Cuban jazz band, back to the states as the opening act of his tour of small and medium sized halls.

This obvious upturn in Stills’ solo career could be the beginning of another peak period in what has been a constantly moving but not always consistent musical journey. At six he received a set of drums and in the ensuing childhood years also learned piano, guitar, and bass while living mostly in Florida and Central America. Latin music, along with Ella Fitzgerald, Chet Atkins, and traditional blues records provided the basis for an initial style. In between military school and a stint as director of his high school orchestra, Stephen also slipped into two teenage rock and roll bands – The Radars and The Continentals. Soon neither Florida State nor New Orleans folk club could match the lure of New York.

Early dues were paid playing small, pass-the-hat clubs amidst famous company in Greenwich Village at night, while earning rent with the Au Go Go Singers during the day.

Initial contacts were made with Richie Furay and Neil Young, then it was out to California.

After selling a couple of early songs and failing a screen test for the Monkees because of crooked teeth, Stills got Furay to come out from New York and form a group. Then while the two them were driving down sunset Boulevard, they pulled up behind a hearse with Canadian plates. Neil Young was at the wheel, Bruce Palmer beside him. Enter drummer Dewey Martin after some initial jamming as the unit picked their name off of a tractor – Buffalo Springfield.

Explosive on stage, the Springfield also released three albums, with Stills authoring the group’s largest national hit, “For What It’s Worth.” Music genealogists rightly begin the country rock family tree with Buffalo Springfield.

After the groups demise, Stills spurned an offer to join Blood Sweat & Tears, recorded “Super Session” (with Al Kooper), and partook in a string of jams that led to Laurel Canyon. Ex-Byrd David Crosby became a constant musical companion. Then, as Crosby told Cameron Crowe in Crawdaddy, there was an evening at Joni Mitchell’s when “Stephen and I were singing ‘Helplessly Hoping’ and all of a sudden this third voice is joining in with us. It was Graham. He’d come with Cass Elliot. It wasn’t more than 30 seconds before we knew exactly what we’d be doing from then on.”

Crosby, Stills & Nash, with the release of their first album in ’69, established the formative groundwork for every barber shop harmony rock group that was been heard from since. Stills’ plea to Judy Collins, “Suite: Judy Blue eyes,” was the LP’s tour the force; “Wooden Ships” was the anthem. With the addition of Neil Young, one of America’s first supergroups was born.

CSN&Y managed to hang together for two tours – highlighted by sizzling electric guitar duels between Stills and Young – and “Déjà Vu”, with rumored internal bickering and ego hassles getting as much attention as the awesome music being produced. The group split up in ’70, and the live Four Way Street became a post-mortem footnote.

Stills’ solo career bloomed impressively as his first LP went gold aided by the single, “ Love the One You’re With,” and the appearance of guests Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton. Stills 2 was even more ambitious and musically varied with harder rockers, tougher blues, and another single, “Change Partners.” But a massive tour with the Memphis Horns found Stills showing insecurities on stage, often, as he puts it, “singing sharp and playing flat.”

The Manassas unit – with Chris Hillman –second in command – forget new musical ground with a tight blend of Latin-rock-country-blues on record and the road. But the shadow of CSN&Y began to return as Crosby, Nash and even Young began dropping in on Stills gigs. A brief CSN&Y reunion try produced only a perspective album cover, and as Manassas spread apart in late ’73, Stills kept on with another combination that included the burgeoning talents of Donnie Dacus (now Chicago’s lead guitarist), and their energetic stage work is presented on the acoustic/electric stage Stephen Stills live.

CSN&Y did regroup for a riotously received ’74 stadium tour, but when no reunion album followed, Stills was back on his own with a jigsaw puzzle of backing players. Dacus became Stills’ closest collaborator, but the albums, “Stills” and “Illegal Stills” and subsequent road shows had only flashes of the raw fire and seemingly inspired quality of previous solo work. And the Stills-Young pairing that was supposed to “terrorize the industry” produced the surprisingly tame “Long May You Run” and an aborted tour.

The Crosby, Stills and Nash reunion in ’77 showed a renewed creative vibrancy and power in Stills’ music – evidenced on CSN and the road shows that criss-crossed the country. This urge carried into another Stills Solo album, “Thoroughfare Gap,” released late last fall[1]. With dashes of churning rock/blues and a lone folk song (the title track, written during the Manassas days), the LP also features a concerted turn into R&B as Stills’ patented Latin rhythm grooves are contemporized with sometimes prominent disco accents. And, as the next CSN album stands…

An afternoon visit to Stills’ Bel Air home on the eve of his solo tour finds him in an electric, overly positive mood. Clad in Lance Allworth’s blue and gold San Diego Chargers football jersey and worn jeans, he takes on the appearance as well as the attitude of an athlete in training. For Stills, this pre-tour activity is probably akin to preparing for a new season.

The present backing players consist of keyboardist Mike Finnigan, rhythm guitarist Gerry Tolman[2], percussionist Joe Lala, bassist George Perry and drummer Joe Vitale. Singer Bonnie Bramlett and drummer Dallas Taylor have been in and out.

Stills and group began rehearsing and recording last fall, got eight new songs in the can, fine-tuned their stage show with four sets at the Roxy in late January and then (following my conversation with Stills) left for the Cuba Festival

What music is Stills performing this tour? With “Thoroughfare Gap” still a relatively new release, I begin our talks wondering if much material from this album is being played live.

SS: There’s some from “Thoroughfare Gap”, like “You Can’t Dance Alone,” and several new songs that haven’t been put out yet. I am also using a whole set nobody has heard in a while, some real old stuff, like “Cherokee” and “Go Back Home,” but none of the music in between. It’s a different show than I‘ve been doing.

Does it mean you are also using a different performing format?

SS: Yes. The acoustic part of the show is going to be cut down a lot, because I am only doing so much time. My instrument is the electric guitar with an amplifier. That’s what I play best and that’s what gets me off. I like to play acoustic, but that’s kind of the CS&N thing. My thing is more R&B oriented.

And this new band is the best I have ever played with, the best band I have ever put together. So I hope full-band sets will suffice and I won’t have to rely so much on the acoustic stuff. It isn’t self-indulgence. I really work and I am trying to entertain. I just like this format.

Do you feel obligated to play your standards, though, like “4+20”and “Change Partners?”

SS: Yes I do, but I focus on different ones. I’ll play “Love The One You’re With” for a couple of years, then I play something else for a couple of years. Right now one of the featured numbers is “For What It’s Worth.” We have got a great new R&B arrangement of it, and it’s cool. I play real funk style, Steve Cropper-type guitar.

The times I have seen you play that song in the past; it’s always been as a medley with “49 Bye Byes.”

SS: Let me tell you, that got real old, real fast.

Have you made any other changes in your show?

SS: Well , I have to lower my keys. Now, I don’t mean to say [gruff voice] I’m getting’ to be an old man or anything, but I just [hits falsetto] can’t quite get up there sometimes. I can’t put too many of those things written in the ionosphere in a row. I’m turning into one of those [voice drops to a bass] Lou Rawls types [laughs] getting’ down into that range.

Were you pleased with the way “Thoroughfare Gap” turned out?

SS: Yes, I like it. That’s why it’s so annoying the album hasn’t sold more. I mean, I have made some turkeys before that have gone 87 with an anchor, and I said, “Oh well.” But this one I really worked hard on. So who knows. In between starting and finishing it, there were two CSN tours and one-and-a-half CSN albums, which tends to confuse matters a bit and disturb the continuity.

Are you sensitive to bad reviews?

SS: Well, I quote Frank Zappa, that famous one… rock critics who can’t write, write about a people who can’t talk, for people who can’t read [laughs]. Kind of cold, but you have to have a sense of humor. The only trouble is that some of these reviews can kill you, ‘cause distributors read that stuff and take it seriously, can ya dig it? I mean, Jiminy Christmas, hey man, a guy’s just trying to make a living. A writer can make up any kind of the shit he wants to… “well, that sounds good” [mimics writing motion].

Most of the criticism of “Thoroughfare Gap” has been about your use of disco.

SS: It’s kind of silly. “Can’t Get No Booty” is really a put on, if you listen to the words. The subtitle of it is “White Dopes On Punk.” What I wanted to do when I cut that thing was to make up the name of a group, like The Nerds or something. Then I was going to just put it out and see what happened. And I bet it would have been a smash, but coming from Stephen Stills I guess it took everybody aback a little.

I noticed Danny Kortchmar co-wrote the song. How did that come about?

SS: We just made it up at the end of a very long and frustrating CSN session. We cut it in about 45 minutes. Then I wrote the verses, dubbed them in the next day, and it was a record.

There are other songs on the album, like “You Can’t Dance Alone,” that represent a more polished disco style.

SS: There are elements of disco I really like – the percussion and guitar. I have played on so many Bee Gees songs I don’t know which ones I played on and which ones I didn’t. Cause Barry [Gibb] is an old friend of mine, and I just sat in and played chickum-chit, chickum-chit, a little wacka-wacka guitar, then said, “Use ‘em or don’t use ‘em, I had a great time. You don’t even have to use my name.”

You did get a percussion credit on “Saturday Night Fever”.

SS: Yeah… Barry Gibb, where’s my platinum album, man, where’s my Grammy?

Now back to your album, you just decided to go more heavily into this style?

SS: Yeah, and I think it will pay off. Maybe some of the tunes weren’t as good as the others I’ve written, but I am just messing around trying to find something new. I can’t do the same thing for eight years. That’s called artistic suicide.

There is a line in the song “Thoroughfare Gap,” ‘…It’s no mater, no distance, it’s the ride.’ This seems to sum up your career.

SS: That’s what it is about. And the title of the album was named after an escape route used during the Civil War. Mosbeys’s guerilla’s used to run through “Thoroughfare Gap” when the felt harassed. They’d just disappear into the Blue Ridge Mountains.

For me, the record represents a little gap between one part of my career and the other. A cut in the pass.

Do you ever feel like you don’t have full control over direction your career is taking, like you’re caught up in the industry?

SS: Yeah, no matter what the contracts say. It just kind of gets out of my hands sometimes. That’s why I decided to go to the Roxy. I thought, “Well, I’ll just mess with everybody,” and proceeded to do so. Nobody knew what to make of me… except the kids. Once all the record company people out of there after the first show, the kids went nuts. It was a smash. And TV was there, all three networks. It was great! It was called “Surprise, you thought I was dead, but I’ll tell you what…”

Do you think about audience adulation and the “star” image at all?

Do you think about audience adulation and the “star” image at all?

SS I think about it, but not too long, because that is a trap. It’s all basically bullshit, and it can destroy your ability with your own talent and art form. I never forget about the art part. I don’t care what they do. They could be crawling over windows, and I’d think, “Hmmm, I guess I did something really far out this time.”

Are you bothered by strangers approaching you in public?

SS: No, that never bothers me at all. Unless I am in a hurry, then I’ll say, “Hey man, I just got to go.” But I guess I am not one that people claw at. They usually ask for an autograph. And hell, I’ll sign an autograph, that’s a part of the gig. I’m never put out by that. I’m flattered. When they don’t ask and when people don’t talk about me is when I’ll get a little paranoid. Just get my name spelled right. That’s Stephen with a ‘ph.’

Going back a few years, when you were a teenager, did music satisfy a need that school couldn’t?

SS: Most assuredly, I think that’s kind of the story of our generation. Of course it did.

So were you able to explore some creativity with music?

SS: Yeah, rather than with the structure that had been designed with the secondary school system.

How do you think your militaristic background has affected your attitude as a musician?

SS: Military school is quite an experience. What can I tell you? I was fairly young. Then I was in ROTC and this and that. And it was always, “You want to take the hill, man?” That kind of attitude has helped me become a trouper.

Why did you go to New York initially?

SS: That was what was happening. But I didn’t stay there for that long. I could never get over all of them dudes from Cambridge singing the blues that I’d grown up with, being all serious about it.

But did you meet a lot of people in New York back then, right?

SS: Yeah, I met Freddie Neil, Tim Hardin, John Sebastian, Cass Eliot, Richie Havens – the list goes on and on. I even met Richard Pryor when he was just starting out. I took in all of the influences by osmosis, I guess.

What about that choral group you were in, the Au Go Go Singers? Isn’t that were you met Richie Furay?

SS: Yes. That was called a straight job, a day job. And I also got a lot of good training out of the cat who was the arranger for that, a fellow by the name of Jimmy Friedman.

Had you started writing songs?

SS: I started when I went to California a few months later. I ran into a draft dodger and wrote that song “Four Days Gone” about him.

But the roots of Buffalo Springfield began East?

SS: Yeah. I’d met Neil up in Thunder Bay, Ontario and we were going to get together. I got him working visas, then couldn’t find him. He’d decided to stay in Toronto and become a folk singer, and I was into becoming a non-folk singer. That’s when I went to California and met Neil two months later in L.A.

Did the Buffalo Springfield click immediately?

SS: Yeah, and it had a lot to do with Bruce [Palmer]. He had a style with the bass. He had that Billy Wyman kind of Motown feel to put underneath everything, and it made it work for me.

I remember that first week at the Whisky and the gigs we did with the Byrds. We could really smoke. That band never got on record as bad, as hard as we were. Live, we sounded like the Rolling Stones! It was great.

How do the Buffalo Springfield recordings sound to you now?

SS: Badly recorded. It was a matter of choking in the studio and not getting the right grooves. It was being young.

Is there a way the group could have stayed together longer than it did?

SS: No. Too much fame and no money. We had some good times, but there was this desperation to make it that kind of chewed at us. And the personalities were pretty extreme too, and being at that age and evolving.

So between Buffalo Springfield and CSN…

SS: It was just hangin’ out trying to figure out what to do next [laughs]. I followed Jimi Hendrix all around the country for a year learning how to play lead guitar. We were great friends, too, and he taught me some great tricks.

Did Hendrix have a different attitude as well as a distinctive technique?

SS: He was just as confused as the rest of us.

Now after this period of jamming the Super Session album and the whole Laurel Canyon scene, what were the initial stages of CS&N like?

SS: We each had a lot of tunes. And we had the acoustic guitars and vocals down. So from there it was a matter of getting it together in the studio. Dallas and I would be working on the arrangements, with Graham in the booth overseeing. Everybody was surprisingly cooperative.

With all the hours of studio work put into recording that first album, you must have had some previous training with arrangements and producing.

SS: During the latter stages of the Buffalo Springfield, we were producing our own songs. And I learned a lot from Bruce Botnick and Jim Messina. Then I started working with Bill Halverson. He would get me up from the board and make me sit down and mix. Halverson taught me all I know about the electronics processes of producing.

You ended up dubbing in all of the lead guitar, organ, and bass on the first album, right?

SS: I wanted to get the best of everybody’s songs. But, overall it was a group effort. Even though I had quite a few surprises for them. They weren’t expecting quite as much track. For instance “Long Time Gone” didn’t have a chorus, just one line, “It appeared to a long time before the dawn.” Dallas and I stayed late one night and made a new track. David came in the next day and loved it. And that was the final version.

That album is where a lot of the forces really came together.

When you decided to tour, did you think of adding any other players before you asked Neil?

SS: We weren’t even thinking of adding Neil. We were looking for a keyboard player. I talked to a fellow in New York, Mark Naftalin, who ended up playing for Butterfield, but I could never pin him down. I really wanted a keyboard player, but the right cat just didn’t come along.

Then I was talking to Ahmet [Ertegun, president of Atlantic Records[3] and he said, “Why don’t you get Neil back in the group?” And I really wanted a musical foil. I wasn’t quite confident enough in my lead guitar playing to carry the whole thing, which, in retrospect, is kind of silly.

Now that I am the lead guitar player in my new band, it’s really neat. It puts pressure on me, makes me play. What can I tell you, except that I’m a late bloomer.

What were the “Déjà Vu” sessions like?

SS: There was a lot of confusion within the band then. We really gutted that one out under a lot of pressure. But it came off. I only wish we could have made a couple more. I was really appalled at us for not sticking it out and keeping together. But everything blew up, so I went to England.

Then you bought Ringo’s estate?

SS: Well, he was the first friend I made over there. He had me up to his house and we started talking about his place in Elstead [a seventeenth century grand Tudor estate]. And Maureen …he was with his wife then … she took me down to see it and I said, “I’ll take it.” I settled on a price with Ringo, then bought it eight months later. When I sold it, I turned it over for 100 percent profit. So, I still haven’t lost my real estate chops.

You have said you didn’t like “Four Way Street?”

SS: Well, my feelings about live albums are that as long as you get the live feel, if there’s some out of tune singing… cheat! I mean the hell with it, we were not in tune on that second chorus. So let’s lay in that second chorus and nobody will know the difference, which they don’t. Then Crosby says, “No man , it’s gotta to be pure, man.” And I just went, “arrgh!” I thought that record was bad.

How did you feel about CSN&Y’s political side back then?

How did you feel about CSN&Y’s political side back then?

SS: We were for a time on the point, so to speak, of that whole movement. All kinds of groups and entertainers have taken turns walking point. For a while it was our turn. I’d come fresh from Latin America after being caught in a revolution in Nicaragua – shot at and missed, shot at and hit – when I saw the Sunset Strip riots, all the kids on one side of the street, all the cops on the other side. In Latin America, that meant there would be a new government in about a month. “For What It’s Worth” was me going, “Psst, I think we’re in trouble.” The troop in Nam took it as their marching song. It became the theme song for the entire Third Marines for a while. From then on, I was kind of known for that. Everybody was looking for a political message in everything I wrote, like I was running for the senate at 24. I said, “Hang on, wait just a minute, I do not know the rules of the Senate.”

And the fact your more recent songs haven’t shown that side…

SS: …doesn’t mean I’m any less political. I am an American, and I reserve the right to speak. Since then I have learned the fine art of lobbying, you see. So I don’t discuss it in public forum. I use the telephone.

But now, the only way left for them dudes to get big bucks in one shot is to throw a concert, have mercy. Sometimes it gets almost as ludicrous as rock meets jock. When I hang out with my football playing buddies, I have more empathy with them than I do with politicians, to a degree.

Do you have done some political benefits, like for David Harris.

SS: I didn’t think he ever had a snow ball’s chance in hell of winning, but he probably would have made a good congressman. I’ve done a lot of benefits for people who’ve gone to Washington and failed miserably. The most work I did was for Gary Hart [senator from Colorado], who turned into a hell of a senator. He’s the liberal voice on armed services, and a good friend.

“I’m not going to let CSN dominate my life. It’s cost me in the past. But I’m always open.”

You first two albums are still viewed as creative peaks and were more commercially successful than any of your other solo efforts. Do you think this had anything to do with when they were released?

SS: Sure, I was at a point where nobody knew what I would do on my own. So people were ready to accept what I was doing.

You were playing with Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix a lot then, right?

SS: Well, Eric was a pretty hard man to pin down at that time. I usually had to drive over to his house and drag him out to get him to play. And Jimi was there today, gone tomorrow. We were going to do an album together. That song “Old Times, Good Times” was the first try at that. After my solo album was turned in, we were going to go back to England and do an album. But… he died.

Did seeing what happened to Hendrix, Joplin and Morrison scare you?

SS: No… no there were a few years there when I was in my “crazed period.” I kind of went off the deep end, too much drinking and drugs. Everybody was saying, “Stills ain’t gonna live four years.” And it was silly. My survival instincts are much too strong for that.

We were all going crazy at the same time. There was a lot of depression and self-indulgent feeling bad. It was really kind of silly, but it happened. In my case, I did what a lot of American men have done for generations: you lose a woman, you pour yourself into a bottle.

Manassas seemed to be your first real solo band.

SS: I tried to create some structure with Manassas. But you have to understand we walked away from a seven million dollar a year operation. So if Manassas had taken off, the vested interests of that seven million dollars would be out.

Manassas seemed to “take off” on stage, especially when you played the whole first side of the double album straight through without a pause.

SS: Hang on, hold tight. Not only can the current band play songs in rapid-fire succession, we take it from “Rock and Roll Crazies” through to “Jet Set,” then go into “Turn Back the Pages!”

With Manassas, I wasn’t playing near what I am now. As far as I’m concerned, my career started about a year and a half ago, when I just bore down on lead guitar and started to really play.

As for the CSN&Y summer tour in ’74, did it have the spark and enthusiasm of the early shows?

SS: It was there, and we had some thundering good shows. Neil and I were into playing outdoors and really into the whole scene. I remember driving into the Kansas City ballpark. Neil and I were together, and he said, “Hey, remember a few ago when we talked about playing baseball stadiums and everybody laughed at us?” We played to eleven million people in one summer.

Were you disappointed when that reunion album failed?

SS: Yes, but I guess it wasn’t right. Maybe it will be right again, I don’t know. Now I’m just going to carry on what I’m doing, because this band I have now is just monstrous.

So are there things you can do with this band that you wouldn’t attempt with CSN&Y?

SS: These guys have been playing for 20 years and they’re really professional. Everybody can be happy with a structured arrangement in this band. They know when their solos are coming, 24, 64 bars. I’ll call an audible, make a little gesture, and everybody knows what I’m saying. It’s a great relief for me, because now I can really play because everything else is so damn tight.

What ever happened to “Stolen Stills,” an album you were supposed to release a few years ago?

SS: That was just a bunch of songs I ended up not using over the years. I’d either run out of room on a particular album, or they weren’t quite up to snatch. I’m going have to take some time off one of these days and go through all my old tapes again and figure out what’s there.

Were the “Stills” and “Illegal Stills” albums and bands satisfying?

SS: Almost. Close, but no cigar. There was always either an extra guy we didn’t need, or something missing. There was always something not quite right with them.

If you were able to do that Stills-Young band album again, would you have done it differently?

SS: Yes, but I can’t put my finger on how. Basically, Neil had his attitude about the record, and I had mine. We were close, but we really could have concentrated harder. To me it was a question of, for expediency or whatever, cheating he songs. The road to hell is paved with good intentions. And it never got beyond the intentions.

When the Stills-Young tour fell apart and your marriage (to French singer Veronique Samson) was dissolving, what kept you going?

SS: What kept me going will tell you a little bit more about Stephen Stills. Just think about it, answer your own question, and it will tell you about why I’m not going to kick off.

So next you went into the studio and those songs from CSN evolved, “Run From Tears” and “I Give You Give Blind?”

SS: All I can remember is the broken heart and the futility of the situation. I can’t remember how the songs evolved, just that they did. There’s a point where you just… you suck it in and say, “I’m gonna take the hill.” If there is something to the mythology of a “star,” I’d like to think I set some example with that kind of courage, because it took everything that I had. But I’ll be damned if I’m gonna let something stop me.

Do you ever worry about getting too close to or too personal with your songs?

SS: The way I took at it is, that’s kind of the job, to share your feelings with people. Maybe something I’ve felt or been through will help them deal with a similar crisis or just make them feel not quite so alone.

Can you think of many songs where you have really surrounded a personal feeling?

SS: I have to look at a few titles. “Open Secret” was a very personal statement. “Thoroughfare Gap” is a song that has to do with encapsulating a personal feeling. And I wrote a song about skin diving [“Black Corral”] that no one seemed to notice, but I guess it was kind of esoteric.

What were you feelings about CSN, the third time around in ’77?

SS: I’ll let the music speak for itself.

Is there a collaboration going on now?

SS: I haven’t seen ‘em.

Is jamming still a pastime of yours?

SS: Well, I got together about a year ago with Ronnie Wood, and Keith Richard in New York. And we just jammed for hours and hours. There were some interesting ideas, and had we had a rhythm section, we could have done something. I’ll always love the Stones.

Eric Clapton has said that if you had show up a week earlier in Miami back in ’74, you might have done an album together. Is that still a possibility?

SS: Yes, but a lot of it has to do with Robert [Stigwood, president of RSO]. The same thing applies to Barry Gibb and me. We have a nice, friendly relationship. And we wrote a song together some day. Then Robin – all three of them – fell in and we sang the chorus one evening in four part harmony and everybody went, “Oh, oh we better not, this would be too much to deal with.” Gorgeous sound, though.

When I got my rep during the crazy years, a lot people came up with an impression of me as being someone incredibly difficult to deal with. Not as much as dealing with a perfectionist [laughs]. But people make there erroneous assumptions about me, and it kind of gets in the way. I’d love to sit down with Eric right here in this room and we could make an album in about a week. It’s still a possibility, we’re still friends. Here’s to whatever happens next.

Where does CSN ’79 stand in relation to your present solo career?

SS: I’m not going to let CSN dominate my life. It’s cost me in the past. But one does not preclude the other, and I’m always open.

So what’s your current motivations, your next goal?

SS: There’s a new song that I’ve written with “Chocolate” [George Perry] called “Dangerous Woman on the Loose.” That’s kind of what is motivating me right now. I just want to get down and get bad, and have a band, and have my style evolve to the point where everybody forgets about all the other stuffs”.

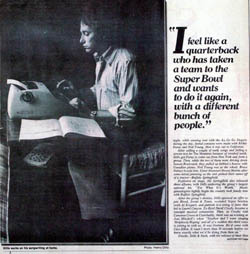

I feel like a quarterback who has taken a team to the Super Bowl and wants to do it again, with a different bunch of people. It’s probably an impossible dream, I know, because people won’t forget the past. Still, I’d just like to supercede what I’ve done with David and Graham with something equally significant, and exciting, and new.” □

© Dave Zimmer, April 6, 1979

Notes from 2007:

Notes from 2007:

[1] 1978

[2] Dave Zimmer: Gerry Tolman later became manager of Stephen Stills and CSN. He died in a car accident in Los Angeles on December 31, 2005.

[3] Dave Zimmer: Ahmet Ertegun was CSN’s “spiritual godfather.” He passed away in December 14, 2006 in New York City due to injuries suffered in a fall at a Rolling Stones concert earlier in the year.